Did you know that food fraud has been clearly illegal under US food laws since at least 1938? Did you know that it is a compliance requirement to conduct a food fraud hazard analysis? The regulatory text is provided below, including ‘adulterated foods’ and also ‘misbranded foods.’

FSMA ‘Hazard Analysis’ Compliance Requirements

There is often a lack of awareness that the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) specifically identifies food fraud – or hazards that are ‘intentionally introduced for purposes of economic gain’ – as a compliance requirement.

21 CFR 117.130 Hazard analysis:

“(a,1) you must conduct a hazard analysis to identify and evaluate… known or reasonably foreseeable hazards…”

“(a,2) The hazard analysis must be written regardless of its outcome”

“(2) Known or reasonably foreseeable hazards that may be present in the food for any of the following reasons:”

“(b,1,i) The hazard occurs naturally;”

“(b,1,ii) The hazard may be unintentionally introduced; or”

“(iii) The hazard may be intentionally introduced for purposes of economic gain.”

FSMA ‘Hazard Analysis’ by Function or Work Process

Building on the basic hazard analysis requirement, FSMA identifies specific business activities that ‘must consider’ food fraud vulnerability. To be clear, this expands from the raw materials or ingredients through all process steps, manufacturing, related handling, storage, and distribution. The emphasis is all the way to the ‘finished food for the intended consumer.’ Remember, a hazard analysis must be conducted to define that there is NOT a threat. “The hazard analysis must be written regardless of its outcome” – essentially, you can’t say you do NOT have a problem until you conduct the ‘hazard analysis.’

21 CFR 117.130 Hazard analysis:

(c,2) The hazard evaluation must consider the effect of the following on the safety of the finished food for the intended consumer:

(i) The formulation of the food;

(ii) The condition, function, and design of the facility and equipment;

(iii) Raw materials and other ingredients;

(iv) Transportation practices;

(v) Manufacturing/processing procedures;

(vi) Packaging activities and labeling activities;

(vii) Storage and distribution;

(viii) Intended or reasonably foreseeable use;

(ix) Sanitation, including employee hygiene; and

(x) Any other relevant factors, such as the temporal (e.g., weather-related) nature of some hazards (e.g., levels of some natural toxins).

FDA Public Comments on Food Fraud Compliance

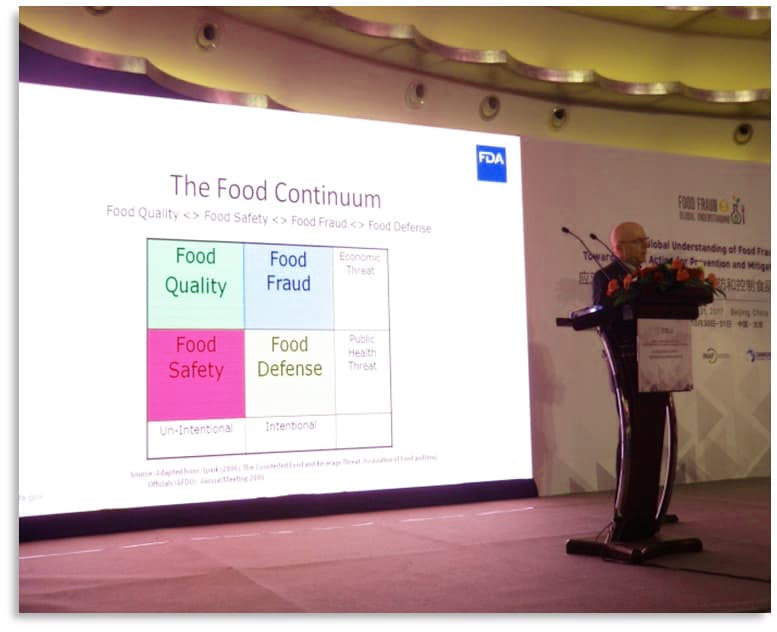

This FDA ‘current thinking’ was publicly presented in 2017 by Acting FDA Commissioner Dr. Ostroff, which was at the start of the global food fraud awareness. The ‘current thinking’ is actually the same as it was back in 1938 and now in 2024. The underlying Food Drug & Cosmetics Act (FDCA) concepts and requirements have not changed. FDA presented ‘current thinking’ to clarify the compliance requirements.

“Current FDA Thinking: FDCA (Dr. Ostroff, Acting Commissioner of FDA), April 5 & October 30, 2017 (Beijing)

Overview

- All types of Food Fraud are illegal.

- FDCA: Adulterated Foods, Misbranded Foods

- To determine “hazards that require a preventive control,” an assessment for all types of fraud is needed.

- Addressing Food Fraud is NOT covered in the FDA Food Defense plans.

Further Clarification

- “In circumstances where no regulatory agency has unlimited resources, where and how does EMA fit into a list of priorities?” Response: public health hazards

- The FDA presentation used the Food Risk Matrix to define the differences in food risks (See Figure)

- The focus of inspections is on product that is in commerce”

Cited FDA definition of EMA then presented the Food, Drug & Cosmetics Act “Regulatory Response”:

- “Adulterated foods [Note; the act provides nine types of adulterated foods]

- Section 402 (a) of the FD&C Act (21 USC 342): “If it bears or contains any poisonous or deleterious substance which may render it injurious to health.”

- Section 402 (b): “if any valuable constituent has been in whole or in part omitted or abstracted therefrom; or if any substances has been substituted wholly or in part…; or if damage or inferiority has been concealed… or if any substance has been added thereto or mixed or packed therewith, so as to increase its bulk or weight, or reduce its quality or strength, or make it appear better of greater value than it is.”

- “Misbranding [Note: the act provides twenty-five types of misbranding!]

- Section 403(b) of the FD&C Act (21 USC 343 (B)): “offered for sale under the name of another food.”Section 403(a): “labelling is false or misleading”

- Section 403(i): “ingredient labeling”

Takeaway Points

- Since at least 1938 (in the Food Drug & Cosmetics Act), all types of food fraud have been clearly illegal.

- The FDCA definition of ‘adulterated food’ does not need a public health threat and does not require an ‘adulterant.’

- A complete FSMA/ FDCA hazard analysis absolutely covers food fraud incidents (so, not including food fraud is technically non-compliance to FSMA/ FDCA) – fortunately, the current food fraud vulnerability assessment and food fraud prevention strategy concepts appear to cover this requirement.

Reference:

- Ostroff, Steven (2017). A regulator’s view on preventing and mitigating economic adulteration of food, Presentation at the Food

- Spink, John, (2011) Defining the Public Health Threat of Food Fraud, Journal of Food Science.