A big question for data analytics is where and how to begin the process. It is most logical to start with a database of incidents that have occurred that are ‘known knowns’ (you know what they are and that they are in your supply chain now). This provides thorough information to build a ‘model for insight’ into the problem.

Start with the ‘Known-Knowns’

A previous blog post covered ‘Known Knowns? Unknown Unknowns? Know Your Problem Type to Frame Your Response’. When starting to review the food fraud problem, such as completing your first food fraud vulnerability assessment, it is crucial to begin with historical, known incidents. The type of incident could be a ‘known known’ (a specific type of fraud act occurring within a particular supply chain) or a ‘known unknown’ (a specific type of fraud act occurring but you don’t know where or when).

Excerpt from the previous blog post:

Know the Type of Your Risk

- “Simple (known known – e.g., water on the floor): For example, the risk of someone falling if there is water on the floor. You know there is water on the floor, so you know that people can slip and fall. If the incident had occurred, you know that mopping up the floor is an immediate and effective response. Later, it would be good to figure out the system weakness that enabled the water to get on the floor in the first place. If the incident has not yet occurred, but you are concerned, you may try to determine and eliminate the root cause. Also, you may realize that snow may melt off employee shoes during the winter, so that additional floor mats may be applied during the snow season.”

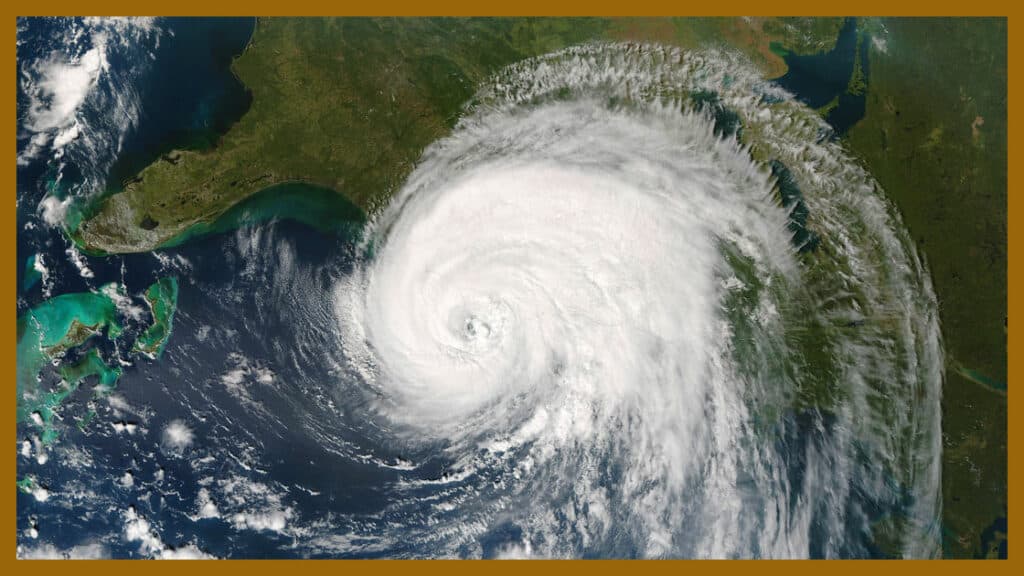

- “Complicated (known unknown – e.g., hurricane season): For example, the risk of supply chain disruptions from hurricanes over a year. You know that hurricanes hit the US gulf coast, but you do not know precisely when they will arrive or the intensity. Still, we know that when there is a hurricane season, a maximum category five could occur, and we know that we can watch the formation of the storms as they cross the Atlantic Ocean. If a category five hurricane is just about to hit your facility, you know that a shutdown and helping your employees seek shelter is an immediate and effective response. (This is specifically familiar to me since I worked for Chevron Corporation in Houston, and our manufacturing plants had very proactive and routine hurricane and weather responses.) Afterward, when reviewing an after-action report, you might realize you should monitor storm development more actively so that you could secure your facility and send your employees home sooner. Later, you may review the most efficient and least disruptive shutdown and startup procedures.”

From the ‘Crime Analysis for Problems Solvers Report,’ a crucial first step is clearly defining your problem. The incident databases are beneficial in determining what problems have occurred that apply to your product or supply chain. “You must be able to describe the type of event that makes up the problem. Problems are made up of discrete events.” There should be a methodical approach to gathering information, which is most efficient if it is based on incident databases and historical horizon scanning.

Gathering Information

The information that is gathered is useful in two primary ways (excerpt):

- Monitor public information for new incidents or trends

- This is a scanning function to gather new information and insight into suspicious activity or potential problems. The processed information would feed into the FFVA.

- E.g., open-source monitoring such as Internet keyword searches, keyword news alerts, or social media monitoring.

- Use available information to identify the root cause of the system weakness

- This is a variation of the other new information or insight gathering that expands to gather enough information on how the fraud act was conducted. The analysis would provide support for selecting countermeasures and control systems

- E.g., open-source searches for vulnerabilities in hot spot analysis and pinch-point review.

Incident Databases and Historical Horizon Scanning

Even if you know nothing about your own food supply chain or the food fraud vulnerabilities, you can start your review with incident databases and historical horizon scanning. It is crucial to at least know what has happened in the past to the ingredients or types of products you procure. By reviewing the past incidents, you can determine what has occurred, and even more critical is the insight into why a system weakness or vulnerability was exploited.

Excerpt from Food Fraud Prevention (Spink, 2019):

Awareness: Incident Review and Fraud Opportunity

The first function or step in the [food fraud prevention strategy development] is “awareness,” which builds upon the related information. Information could be from “incident reviews,” which are known events, scanning, or “horizon scanning,” that could be a wide range of “signals” such as price changes or commodity shortages and “public policy” which includes increased risk of detection or enforcement due to new priority setting. This awareness building is based on the criminology-based science of intelligence analysis. To provide the right type of information or intelligence to assess the fraud opportunity or problem, there is a systematic gathering and analysis of raw data, a process to monitor changes, and then a step to filter and process this into actionable intelligence.

Takeaway Points

- Use incident databases and historical horizon scanning to establish a foundation for your food fraud vulnerability assessment.

- When you add a new supplier or product, review the historical incidents to understand if you have a new or changing vulnerability.

- Regularly review the incident database and historical horizon scanning to see if anything new has occurred – it is also a data point if you do NOT find anything new.